Magic and scribblings

The Codex Gigas also contains some short texts. Among others, these include the confession of sins, a number of spells, a calendar and general-purpose scribblings.

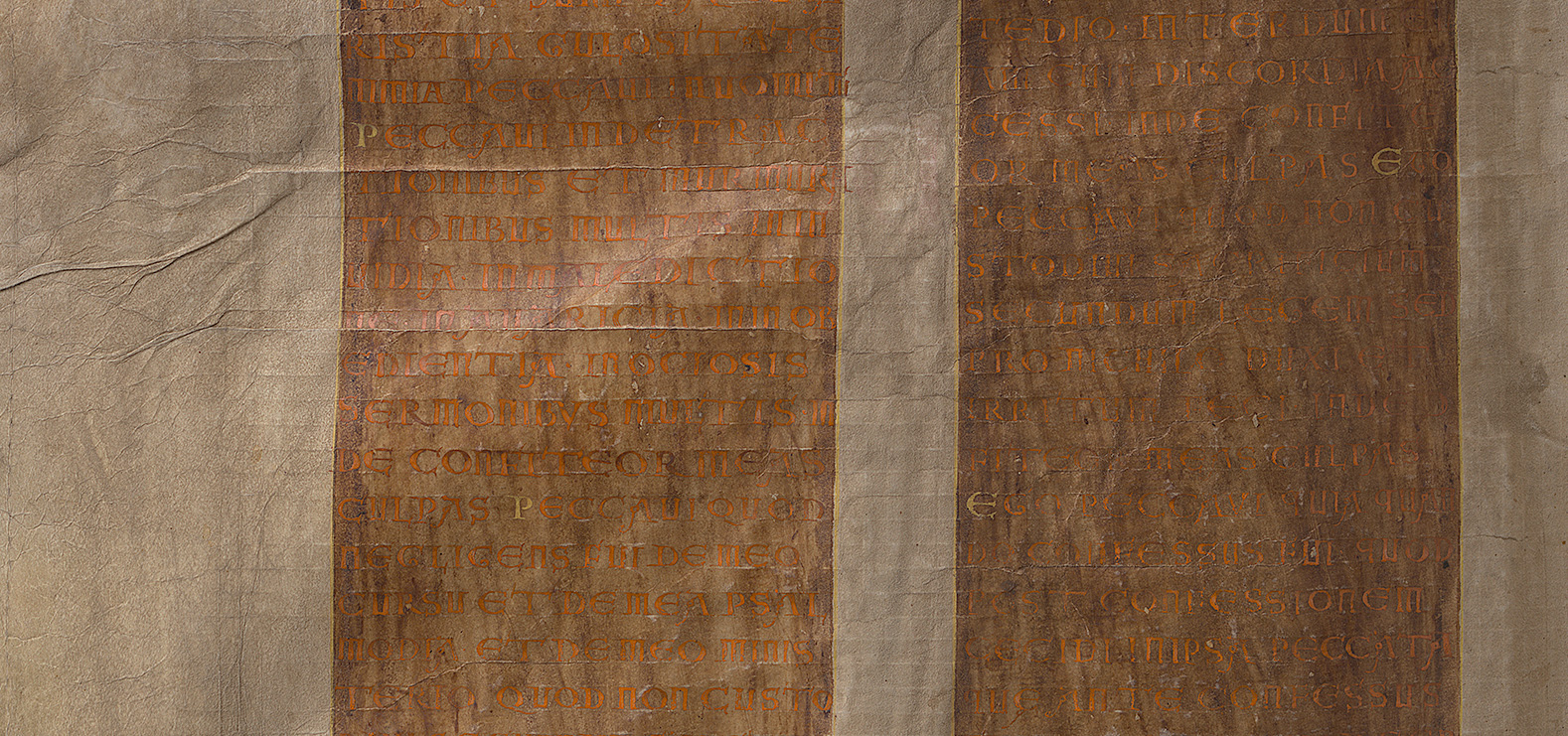

The confession of sins appearing in the Codex Gigas is five pages long.

A churchman confesses his sins

The confession of sins appearing in the Codex Gigas is five pages long and appears just before the spread containing the Heavenly Jerusalem and the Devil. A churchman confesses his sins, ending with prayer for forgiveness and mercy.

Lists of sins could be very long, especially during the early part of the Middle Ages – these were entire catalogues of sins, consisting of a blend of major and minor vices. The large number of sins was meant to stress man's weakness. This method was used to inspire fear of committing wicked deeds.

Spells and magic

The spread appearing after the portrait of the Devil has three spells and two magic formulas. Perhaps they were placed there to counterbalance the Devil. The purpose of the spells is to cure sudden diseases and feverish states, while the formulas describe how to capture thieves using various rituals.

A spell is a religious or magical formula whose purpose is to obstruct or overcome evil, misfortune and disease. In the Middle Ages, spells were used in a variety of contexts, both within and outside the church.

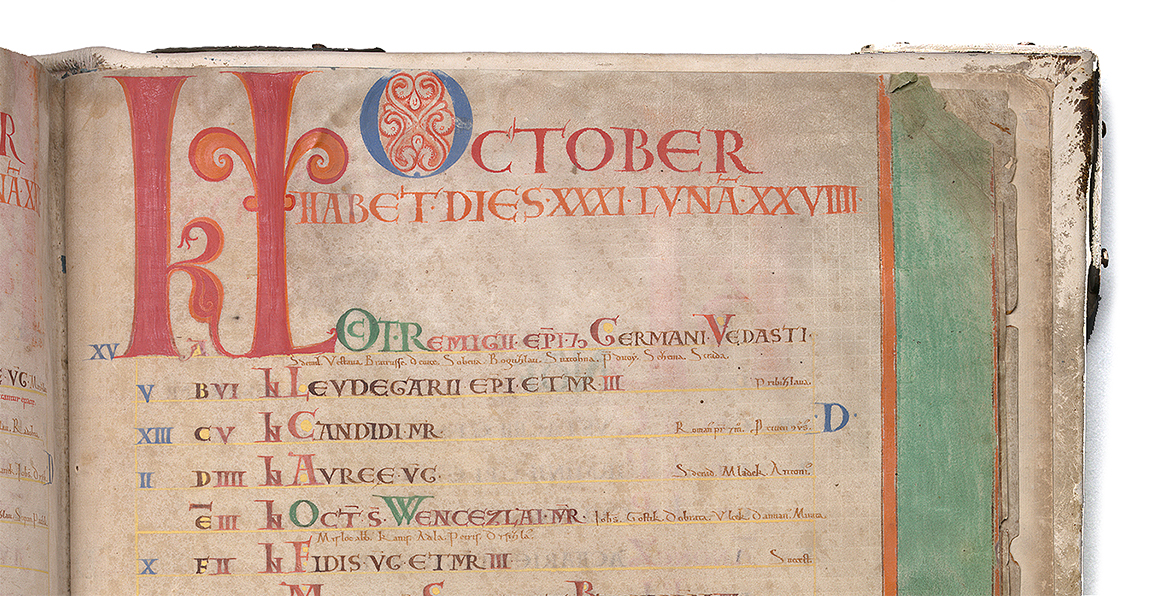

The calendar takes up twelve pages in the Codex Gigas.

Calendar with festivals and dates of death

The final significant short text is a calendar listing the days on which saints were celebrated and those on which the observant were to commemorate the dates of death of people from Bohemia, from both within and outside the church. The calendar reckons dates differently than modern ones do. There were three principal days during each month. The other days of the month were named based on how many days remained until the next principal day.

Names and scribbling

The Codex Gigas contains just over fifty different notes that have been added over the years. A large part of them fall under the "I was here" genre – that is, various people who recorded their names, usually coupled with a short comment. Two Czech researchers wrote down their names as recently as the 1800s.

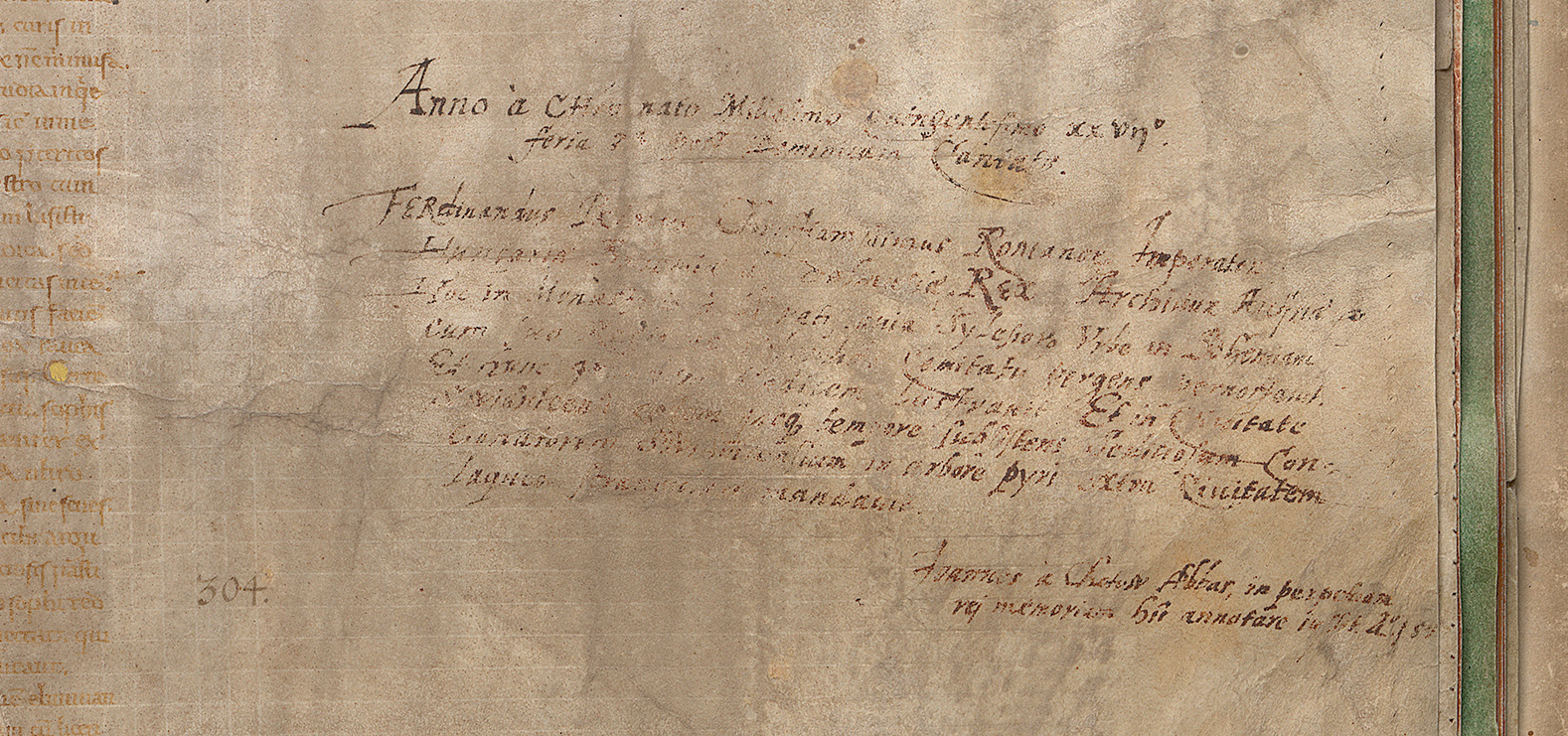

Note on an imperial visit

An example of a subsequent addition is a note from 1527. It was written by the abbot of Broumov Monastery and mentions that Emperor Ferdinand I spent the night at the monastery, which also housed the Codex Gigas at that time. Before arriving in Broumov, he had stayed in the nearby town of Świdnica where he, according to the note, had had “a rebellious preacher hanged from a pear tree outside the city”.

Note on Ferdinand I's visit.